You'll Be Back Lyrics — Hamilton

You'll Be Back Lyrics

You cry in the tea which you hurled in the sea as you see me go by

Why so sad?

Remember we made an arrangement when you went away

Now you're making me mad.

Remember despite our estrangement, I'm your man

You'll be back

Soon you'll see

You'll remember you belong to me

You'll be back

Time will tell

You'll remember that I served you well

Oceans rise, empire fall

We have seen each other through it all

And when push comes to shove

I will send a fully armed battalion to remind you of my love

Da da da da da Da da da da di ya da da da da di ya da

Da da da da da Da da da da di ya da da da da da di ya

You say my love is draining and you can't go on

You'll be the one who's complaining when I am gone

No, don't change the subject!

'Cause you're my favorite subject

My sweet submissive subject

My loyal, royal subject

For ever

And ever

And ever and ever and ever

You'll be back

Like before

I'll fight the fight and win the war

For your love

For your grace

And I'll love you til my dying days

When you're gone, I'll go mad

So don't throw away this thing we had

Cause when push comes to shove

I will kill your friends and family to remind you of my love

Da da da da da da da di ya da Da da da da di ya da

Da da da da da da da da da di ya da da da da da diya

Everybody

Da da da da da da da di ya da Da da da da di ya da

Da da da da da da da da da di ya da da da da da diya

Song Overview

Song Credits

- Album: Hamilton: An American Musical (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

- Release Date: 2015-09-25

- Producers: Bill Sherman, Lin-Manuel Miranda, ?uestlove, Black Thought, Alex Lacamoire

- Writer: Lin-Manuel Miranda

- Genre: Broadway, Pop, Soundtrack

- Instruments: Violin, Viola, Cello, Harp, Guitar, Banjo, Bass, Drums, Synthesizer, Keyboards

- Label: Atlantic Records

- Length: Approx. 3 minutes

- Language: English

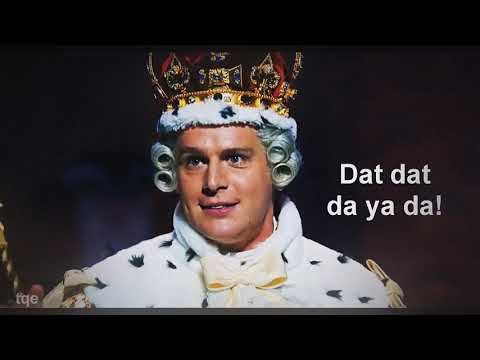

- Vocals: Jonathan Groff & Original Broadway Cast of Hamilton

- Mastering Engineer: Tom Coyne

- Mixing Engineer: Tim Latham

- Conductor & Orchestration: Alex Lacamoire

Song Meaning and Annotations

When Hamilton hits its ironic high note with “You’ll Be Back,” it does more than just provide comic relief—it turns the tables on everything you thought you knew about power, patriotism, and love songs. Sung by King George III, played memorably by Jonathan Groff in the original Broadway cast, this number is a study in contradictions: absurd yet threatening, jovial yet oppressive, and gleefully clingy in a way that’s unsettlingly familiar. From the outset, it’s clear that King George is no typical villain. He’s not a battlefield presence, nor does he engage in any debates or cabinet meetings. Instead, he appears solo, smugly declaring his love—or, rather, his possessive control—over the American colonies.

It’s no coincidence that King George is the only principal character in the original production who is white. In a show dominated by a diverse cast portraying the Founding Fathers and revolutionaries, George stands out as an almost absurd relic of colonial power. Rather than making him a figure for audience identification—as is so often done in mainstream media—Hamilton flips the narrative. He’s the outlier, the outsider, and that’s intentional.

Structurally, all of King George’s songs are solo numbers, and that choice speaks volumes. While the revolutionaries work in harmony, often overlapping in spirited, ensemble-driven pieces that reflect a collaborative (albeit chaotic) republic, George sings alone. He stands as a literal monarch—one voice, one rule. His lone vocal presence starkly contrasts with the chorus of democratic voices in the rest of the show.

King George’s role is designed as a cameo, almost like a curtain call in reverse. With just three brief songs and minimal choreography, the part is manageable for high-profile actors without the grueling prep typical of lead roles. Over the course of Hamilton’s early run, actors like Brian d’Arcy James and Andrew Rannells took turns stepping into the royal shoes, each bringing their own flair. Groff, though, became the definitive version—his lip-synced rendition of “The Schuyler Sisters” during a #Ham4Ham show is now part of theater legend.

Musically, the song opens with a line that slyly mirrors the Beatles' “With A Little Help From My Friends”: “The price of my love’s not a price that you’re willing to pay.” There’s a melancholy familiarity in that phrasing, drawing from decades of pop tradition that has often masked control and manipulation under the guise of romance. It’s a perfect setup for the twisted dynamic between George and the colonies.

Historically speaking, the grievances underpinning the Revolution—most famously, “taxation without representation”—are reflected in this mocking serenade. The colonists’ resentment, often symbolized by the Boston Tea Party, was less about specific tax burdens and more about autonomy and principle. At the time of the Tea Party, the tea tax was practically the only tax left, retained mostly to affirm Britain’s right to impose taxes if it wanted. So, in some ways, the dispute was more about the symbolism of control than the monetary value itself.

The line “Remember we made an arrangement…” carries the petulant tone of a jilted lover—or maybe more accurately, a parent chastising a rebellious child. Early on, Britain took a hands-off approach to the colonies, but as the economic stakes grew, so did the rules and taxes. And as you’d expect, the colonies didn’t take kindly to being micromanaged.

There’s plenty of clever wordplay throughout. The dual meaning of “mad”—as in angry and insane—adds to the delicious unease. The whole song drips with the aesthetic of a controlling love ballad, more in line with Michael Bublé’s version of Leonard Cohen’s “I’m Your Man” than any royal decree. The threats are veiled in charm, the power plays hidden behind honeyed melodies.

The musical arrangement itself underscores this strange blend. The piano gives way to a harpsichord, nudging us into the Baroque pop style of the Beatles, and the staccato rhythm sets a pace that’s both jaunty and ominous. It’s deceptively simple too: monosyllabic rhymes, straightforward vocabulary, and not much sophistication. George’s use of rhyme is notably underwhelming, especially compared to the lyrical gymnastics displayed by Hamilton and company. His lines mostly rhyme “say” with “pay,” “cry” with “by,” and “mad” with “sad.” It’s elementary, almost childlike. The only real exception is “estrangement,” but even that feels like he’s trying too hard. As a lyricist, George just can’t compete. Even little Philip does better.

But perhaps that’s the point. King George isn’t supposed to be clever—he’s supposed to be entitled. His simple language and repetitive structure reflect the stagnant, unchallenged world of hereditary rule. It’s almost laughable. In fact, it is laughable—deliberately so.

And yet, despite all that, there’s menace behind the smile. The line “I’ll send a fully-armed battalion to remind you of my love” is as chilling as it is hilarious. The comedic setup of the song—this overly theatrical, slightly effeminate king pouting about betrayal—suddenly sharpens into a very real threat of violence. It’s that moment when a love song turns from clingy to unhinged, a tonal pivot that’s both deeply effective and disturbingly accurate.

This sudden shift makes King George’s character even more fascinating. There’s a theatricality in his descent into passive-aggressive tyranny that calls back to characters like King Herod in Jesus Christ Superstar. As the music dances forward, the audience laughs—and then shudders.

Later in the song, George croons, “You’ll be back, like before,” dropping the comma this time. It’s subtle, but the implication is strong: he’s not waiting for reconciliation—he expects domination. His vision of the future is a clean return to the old status quo, as if the rebellion, the bloodshed, the Declaration—none of it ever happened. That’s more than arrogance. That’s delusion.

The American Revolution wasn’t just a political event—it was also a cultural rupture, powered by Enlightenment ideals that fundamentally challenged the divine right of kings. Thinkers like Locke and Rousseau argued that authority should rest with the people, and that rulers who abused power ought to be overthrown. King George’s lament that he “made an arrangement” suggests he still sees himself as a benevolent provider, bewildered by the colonists’ ungratefulness. But to the revolutionaries, he wasn’t a jilted lover—he was a tyrant.

There’s also a historical irony in George’s plaintive tone. Just a couple of decades earlier, Britain and the colonies fought side by side during the Seven Years’ War (known here as the French and Indian War). Victory in that war helped solidify British control over North America, but also planted the seeds of colonial dissatisfaction. The same young officers who led those battles—George Washington among them—would soon turn against the crown.

Miranda plays with this dramatic irony musically as well. On the word “rise,” the melody dips, and on “fall,” it ascends—an intentional inversion, borrowed from the Sherman brothers' “A Spoonful of Sugar.” This dissonance between word and note echoes the larger irony of the scene: a powerful monarch completely unaware of his shrinking relevance.

The line “Oceans rise, empires fall” carries additional weight. While it likely wasn’t meant to signal climate change, it does reference the natural rhythm of history—empires expand, and then they collapse. In fact, the line may even evoke the story of King Cnut, an 11th-century monarch who demonstrated the limits of his power by showing that he couldn’t stop the tide. King George, it seems, missed that lesson entirely.

By the end of the song, George’s love has fully morphed into domination. “You say your love is draining, and you can’t go on” is followed by a dramatic synth riff that mimics the style of The Beatles—specifically Paul McCartney. The entire number is laced with these British pop allusions, even borrowing vibes from Penny Lane and Getting Better. It’s a musical wink that connects the imperialism of old with the cultural imperialism of the British Invasion.

When George declares, “You’ll be the one complaining when I am gone,” he’s not just suggesting that the colonies will miss him—he’s asserting that they can’t survive without him. His view of leadership is deeply paternalistic. He sees America as a dependent child or a wayward lover—someone who doesn’t know how good they had it. In his mind, they’ll come crawling back because they have no other choice.

This twisted emotional manipulation crescendos with the repeated use of the word “subject.” “Forever and ever and ever and ever and ever…” becomes almost ritualistic. He draws on the language of religious devotion, perhaps invoking his role as head of the Church of England. But it’s all hollow, exaggerated—church service meets comedy sketch.

In many ways, “You’ll Be Back” is the breakup song from hell. George isn’t interested in mutual love—he wants praise, obedience, submission. And he’s not subtle about it. When he sings, “You’ll be back, time will tell,” the double meaning cuts deep. On the surface, it’s a classic lovesick line. But underneath, it’s the voice of empire, of a ruler who can’t fathom a world where he isn’t at the center of it all. It’s less about heartbreak and more about control disguised as nostalgia.

And the thing is—time does tell. George’s repetition of the phrase across his three songs becomes almost prophetic. While everything else in the relationship between Britain and the colonies changes, George’s tone stays eerily consistent. He doesn't evolve, doesn't reflect. He just waits. That’s part of what makes the joke land so effectively—he is, quite literally, history refusing to move on.

As we follow him deeper into his warped fantasy, it becomes clear: this isn’t just a king expressing grief. It’s a king unraveling. He sings about sending troops “to remind you of my love,” turning declarations of affection into militarized threats. The moment gets a big laugh from the audience, but there’s something undeniably disturbing underneath the humor. It’s a reminder that for all its style and comedy, this is still a song about war, conquest, and psychological abuse.

King George’s descent into madness isn’t just metaphorical, either. Later in life, the real George III suffered bouts of severe mental illness, which have since been dramatized in The Madness of King George. He was known to talk incessantly, foam at the mouth, and experience hallucinations. His episodes became so unmanageable that his son was appointed Prince Regent in his place. Whether due to porphyria, arsenic exposure, syphilis, or a combination of mental health disorders, the king’s decline was a very public affair—and it became inseparable from his legacy as “the mad king who lost America.”

That subtext lingers behind the line “When you’re gone, I’ll go mad.” It plays like an exaggerated lament, but to anyone who knows history, it lands with a jarring punch of recognition. Miranda even mentioned it directly in an interview: “There are nerds who laugh when King George says, ‘When you’re gone, I’ll go mad,’ because they know King George went f*ing mad.”

There’s also a line that breaks from the song’s established melody—the moment when he says, “I will kill your friends and family to remind you of my love.” Up until this point, the threats have been veiled in cheeky smiles and bouncy rhythms, but this sudden melodic deviation strips the charm away and reveals the cruelty beneath. It’s the kind of tonal rupture that shakes the audience for a second, right before the music glides back into its deceptive cheer.

The electric guitar riff that follows is lifted straight from the Beatles’ “Getting Better,” cementing the song’s British pop identity. And when George invites the entire cast—and by extension, the audience—with a giddy, “Everybody!”, it’s both ridiculous and authoritarian. The ensemble scrambles into place on stage, and the tension between theatricality and tyranny tightens again. You laugh, but only because the alternative is unsettling.

In a way, King George’s songs are the perfect satire of monarchy. They’re catchy, charming, ridiculous—and steeped in centuries of colonial violence. They showcase entitlement dressed up as devotion, and threats sweetened by melody. By the end of his number, George hasn’t changed or grown or understood anything. He’s still waiting. Still certain. Still singing.

And somewhere, with his crown slightly askew and that smug smile plastered on his face, he truly believes they’ll be back.

If breakups had crowns and powdered wigs, "You’ll Be Back" would be the national anthem. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s satirical jewel from Hamilton dresses imperial tyranny in Beatles-esque whimsy. Sung by King George III — portrayed with velvet pomp and a manic grin by Jonathan Groff — the number is less a love song than a letter bomb in falsetto.

Sarcasm as Strategy

King George croons:

"You'll be back, soon you'll see / You'll remember you belong to me"

He's the jilted lover you can't shake, the colonial sugar daddy turned stalker. The framing is pure 1960s bubblegum pop, but the undertone is Napoleonic iron. It's the sound of empire smiling while loading a musket.

There’s an elegant menace beneath the melody. With lines like:

"I will send a fully armed battalion to remind you of my love"

…the song turns love into a euphemism for domination. That’s the genius of it. The more absurd and lovelorn the tune sounds, the more sinister the message underneath.

Musical Style as Political Satire

Unlike the rest of Hamilton’s hip-hop and R&B tapestry, George’s songs are purely British Invasion — think The Beatles with bloodlust. The jarring musical style highlights the cultural and ideological chasm between the colonies and the crown. It’s like throwing a royal garden party in the middle of a street protest.

Repetition, Repetition, Repression

The chorus is repeated with minor lyrical changes, but no musical evolution. Just like monarchy — rigid, cyclical, unchanging until death. Even the nonsensical "Da-da-da-dat" refrains parody the depthlessness of autocratic pomp. George sings alone, always, reinforcing his isolation and autocracy compared to the communal, overlapping voices of the American characters.

Similar Songs

-

“Herod’s Song” – Jesus Christ Superstar

A similarly flamboyant, sardonic solo by a morally questionable monarch. Herod and George both ooze camp and menace. Their songs interrupt heavier narratives with comic relief that slowly turns sour. -

“I'm Still Standing” – Elton John

While not politically charged, Elton’s anthem of personal resilience has a melodic cheekiness that matches King George’s tone. Both embody perseverance with a wink and a snarl. -

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” – The Beatles

Cheery and melodic on the surface, but chilling when you read the lyrics. Like "You'll Be Back", it hides violence behind singalong-friendly sweetness. A masterclass in tonal misdirection.

Questions and Answers

- Why is “You’ll Be Back” styled like a pop love song?

- The song uses the love song format to parody colonial possessiveness. By making imperial domination sound like a jilted ex-boyfriend’s ballad, it exposes the absurdity of George’s entitlement and emotional manipulation.

- What does the repeated line “I will kill your friends and family to remind you of my love” signify?

- It’s the climax of the song’s dark joke. By placing grotesque violence in the middle of a catchy chorus, it lampoons how tyranny cloaks cruelty in the language of care.

- Why does King George sing alone?

- His solos emphasize monarchy's isolation and egocentrism. Unlike democratic discourse, which involves many voices, George rules — and sings — alone, reinforcing the musical’s ideological contrast between monarchy and republic.

- What inspired Lin-Manuel Miranda to write this song?

- The song was sparked during his honeymoon, with Hugh Laurie jokingly saying “Aww, you’ll be back.” Miranda turned that quip into the song’s concept — a tyrant writing a delusional love letter to his revolting colonies.

- How does the song reflect historical context?

- Its tone mirrors King George III’s 1775 speech to Parliament, where he denounced American rebellion and promised military force. Miranda filtered these historical sentiments through pop sarcasm, making tyranny theatrically absurd.

Awards and Chart Positions

- Certified Platinum by the RIAA on December 10, 2020

Fan and Media Reactions

“236 years and I’m still not over it.” – King George |||, YouTube Comment

“This is basically a pop breakup song about America and Britain. Absolutely brilliant satire.” – BoundaryBreaker

“The ‘I will kill your friends and family’ line cracks me up every time. Comedy and horror all in one.” – ilovehamilton

“I sang this to my boyfriend. He now bans musicals in the car. Worth it.” – jaedyn7100

“The repetition, the solos, the ‘da-da-da’s… monarchy never sounded so petty.” – RuojingZhang

Jonathan Groff’s unblinking, velvet-voiced portrayal makes "You’ll Be Back" a showstopper — a glittering, gaslighting tantrum with a crown. It’s satire sharpened to a royal point. Or rather, a royal jab in the ribs with a velvet glove.

Music video

Hamilton Lyrics: Song List

- Act 1

- Alexander Hamilton

- Aaron Burr, Sir

- My Shot

- The Story of Tonight

- The Schuyler Sisters

- Farmer Refuted

- You'll Be Back

- Right Hand Man

- A Winter's Ball

- Helpless

- Satisfied

- The Story of Tonight (Reprise)

- Wait For It

- Stay Alive

- Ten Duel Commandments

- Meet Me Inside

- That Would Be Enough

- Guns and Ships

- History Has Its Eye on You

- Yorktown

- What Comes Next?

- Dear Theodosia

- Non-Stop

- Act 2

- What'd I Miss

- Cabinet Battle #1

- Take a Break

- Say No to This

- The Room Where It Happens

- Schuyler Defeated

- Cabinet Battle #2

- Washington on Your Side

- One Last Time

- I Know Him

- The Adams Administration

- We Know

- Hurricane

- The Reynolds Pamphlet

- Burn

- Blow Us All Away

- Stay Alive (Reprise)

- It's Quiet Uptown

- The Election of 1800

- The Obedient Servant

- Best of Wives and Best of Women

- The World Was Wide Enough

- Finale (Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story)

- Off-Broadway musical numbers, 2014 Workshop

- Ladies Transition

- Redcoat Transition

- Lafayette Interlude

- Tomorrow There'll Be More Of Us

- No John Trumbull

- Let It Go

- One Last Ride

- Congratulations

- Dear Theodosia (Reprise)

- Stay Alive, Philip

- Ten Things One Thing